picture of jackson and fish

My life as a fisheries scientist

My research on fish populations has taken me to different places on the globe and I enjoy sharing those stories.

Monday, March 11, 2013

Saturday, May 19, 2012

Petition to List 5% of Freshwater Fish in US

|

| Watersheds with 10 or more at-risk fish and mussel species are concentrated in the Southeast, reflecting the extraordinary species diversity of rivers and streams in this region. (Rivers of Life) |

The dynamic physiographic provinces spanning the Southeastern United States, comprised of mountains, piedmont, and coastal plains, combined with the historic absence of ice sheets and glaciers, created incredibly diverse aquatic ecosystems and species. Altered and fragmented habitats, invasive species, overharvest, disease, and pollution are threatening that diversity, putting aquatic ecosystems at risk.

A petition to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) was made by The Center of Biological Diversity in April of 2010 to list 404 aquatic, riparian, and wetland species from the Southeastern United States as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act. This petition was a result of a 1994 USFWS request favoring multi-species listings that are appropriate when several species have common threats, habitat, distribution, landowners, or features that would group the species and provide more efficient listing and subsequent recovery.

|

In September 2011, the USFWS found that protection of 374 of the 404 may be warranted and will conduct an in-depth status review of each species. Eighteen of the remaining 30 species were already listed as candidates for protection, and the final 12 species were fish that did not have substantial scientific or commercial information to move forward.

The 374 species being considered include 89 species of crayfish and other crustaceans, 81 plants, 78 mollusks, 51 insects, 43 fish, 13 amphibians, 12 reptiles, 4 mammals and 3 birds, and are found in 12 states: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia. With just over 800 described freshwater fish species in the United States, the 43 included fish species represent 5% of that total, indicating the strong implications of this petition and review for fisheries research. Yet, the Association for Biodiversity further suggests an additional 250 freshwater fish species at risk, demonstrating the need for further attention in other regions.

Those in the scientific community with expertise concerning the status of a species under review are asked to submit information in regards to:

The species’ biology, range, and population trends, including:

(a) Habitat requirements for feeding, breeding, and sheltering;

(b) Genetics and taxonomy;

(c) Historical and current range, including distribution patterns;

(d) Historical and current population levels, and current and projected trends;

and

(e) Past and ongoing conservation measures for the species, its habitat, or both.

List of 43 fish species:

Northern cavefish (Amblyopsis spelaea),

bluestripe shiner (Cyprinella callitaenia),

Altamaha shiner (Cyprinella xaenura),

Carolina pygmy sunfish (Elassoma boehlkei),

Ozark chub (Erimystax harryi),

Warrior darter (Etheostoma bellator),

holiday darter (Etheostoma brevirostrum),

ashy darter (Etheostoma cinereum),

Barrens darter (Etheostoma forbesi),

smallscale darter (Etheostoma microlepidum),

candy darter (Etheostoma osburni),

paleback darter (Etheostoma pallididorsum),

egg-mimic darter (Etheostoma pseudovulatum),

striated darter (Etheostoma striatulum),

Shawnee darter (Etheostoma tecumsehi),

Tippecanoe darter (Etheostoma tippecanoe),

trispot darter (Etheostoma trisella),

Tuscumbia darter (Etheostoma tuscumbia),

Barrens topminnow (Fundulus julisia),

robust redhorse (Moxostoma robustum),

popeye shiner (Notropis ariommus),

Ozark shiner (Notropis ozarcanus),

peppered shiner (Notropis perpallidus),

rocky shiner (Notropis suttkusi),

saddled madtom (Noturus fasciatus),

Carolina madtom (Noturus furiosus),

orangefin madtom (Noturus gilberti),

piebald madtom (Noturus gladiator),

Ouachita madtom (Noturus lachneri),

frecklebelly madtom (Noturus munitus),

Caddo madtom (Noturus taylori),

Chesapeake logperch (Percina bimaculata),

coal darter (Percina brevicauda),

Halloween darter (Percina crypta),

bluestripe darter (Percina cymatotaenia),

bridled darter (Percina kusha),

longhead darter (Percina macrocephala),

longnose darter (Percina nasuta),

|

| Broadstripe shiner |

bankhead darter (Percina sipsi),

sickle darter (Percina williamsi),

broadstripe shiner (Pteronotropis euryzonus),

bluehead shiner (Pteronotropis hubbsi), and

blackfin sucker (Thoburnia atripinnis)

-Patrick Cooney

Further reading:

-Patrick Cooney

Further reading:

(Fish pictures from fishbase.org)

Jumping Sturgeon

As the mist swirls from the tannin stained Okefenokee Swamp water, prehistoric behemoths lurk below waiting to “maim”, “strike”, “clobber”, and “attack." Lacking teeth, they utilize their sheer size and sharp bone-like protrusions against us humans. Weighing up to 220 pounds and reaching lengths of eight feet, the stealth attackers have struck people in boats traveling at 40 miles per hour. Boaters beware, Gulf sturgeon are out to get you!

|

| Tim Ross |

Recent headlines exclaim Maim!, Strike!, Clobber!, and Attack!, inferring the highly threatened fish are the aggressors and that the fish are fighting back. The words grab attention (just look at the title of this article), but do not accurately characterize these docile animals. When removed from the water for research, the sturgeon often lie motionless in the boat, as if being out of water calms them (check out the picture below). One is not able to witness their true power until returning them to the water.

|

| The author conducting research with a Gulf sturgeon from the Suwannee River, Florida. |

|

| The Suwannee River is at the far East of the Gulf Sturgeon's current range (USFWS) |

|

| Sharp scales called "scutes" line the body of Gulf sturgeon (Associated Press) |

|

| A close call with a Gulf sturgeon (University of Florida IFAS) |

|

| (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission) |

-Patrick Cooney

Further Reading:

Why do sturgeons jump? Insights from acoustic investigations of the Gulf sturgeon in the Suwannee River, Florida, USA

Living With Gulf Sturgeon: Map of confirmed strikes, Awareness Materials, Press, and FAQ

Airplane Trout Stocking

|

| Duane Johnson |

Jagged mountain tops towered over us directly out the window as we took our initial dive into a deep chasm in search of our drop zone. “Let ‘em go!” were the only words the pilot directed at me that early autumn day over the piercing sounds of the low altitude alarms. As the emerald treetops gave way to cobalt glacier formed lakes of the Sierra Nevada’s western slope, an instant rush of air flooded the cabin when I pushed the lever, opening the door in the belly of the plane. We pulled out of our dive-bomb and banked hard left, as if avoiding return fire, to look out the window and ensure our payload had hit its intended mark. An “affirmative” from the pilot to the copilot meant a job well done, and it was off to our next target.

|

| Field and Stream |

The peaks of the high Sierra’s, named by Spanish explorers for their resemblance to the teeth of a saw, have limited road access. Trout stockings in remote lakes, intended to increase recreational angling opportunities, were initiated in the mid 1800s, and painstakingly carried out by barrel carrying mule trains. Following World War II, an abundance of planes and pilots led to widespread trout stocking by aircraft throughout the Rockies and Sierra Nevadas.

Stocking airplanes are outfitted with numerous small compartments that hold trout fingerlings intended for each target, and a final delivery hopper is fed through tubes by switches and levers. Altitude, shoreline shape, surrounding topography, wind speed, and wind direction must all be accounted for in the approach, and the recent incorporation of Global Positioning Systems has increased target identification and dropping accuracy.

|

| Mule train carrying trout fingerlings for stocking in Idaho circa 1944 (cardcow.com) |

|

| Field and Stream |

|

| Aerially stocked trout contributed to the reduction of endangered mountain yellow-legged frog populations in glacier formed high mountain lakes of the Sierra Nevadas. |

-Patrick Cooney

Videos of airplane stocking (from Field and Stream):

Further reading:

Eradicating an Invasive Predator

It was like the loud crash of an old Batman episode: BOOM!! KAPOW!! The shock waves from the explosion tore through the water and blew the fish apart from the inside by fatally rupturing the gas filled swim bladder, the organ designed to provide buoyancy in the water column.

Desperate times and previous blunders had led the California Department of Fish and Game to attempt some unusual eradication measures. This time, detonation cord laying along the bottom of the lake was the destructive implement of choice. Despite an amazing display of pyrotechnic force and some close proximity fish evisceration, the majority of the invasive pike continued with their mission of consuming the fat laden native trout.

Portola is a sleepy town tucked away in the Northern Sierra Nevada Mountains, best known for a world class rainbow trout fishery in Lake Davis. The story goes that an angler looking for an additional angling opportunity mysteriously slipped a bucket of a few non-native northern pike into the lake. Before long, a significant decline in trout and a dramatic increase in northern pike created a panic issue.

|

| (Credit) |

Without much input from the community, the California Department of Fish and Game decided to employ thousands of gallons of rotenone, a piscicide, to eradicate the voracious predator from its confines of the reservoir before it escaped downstream and began feeding on struggling populations of salmon and steelhead.

|

| (Credit) |

The town became incensed and protested the act because the lake also served as the town’s water supply. People chained themselves to buoys and threatened the lives of piscicide applicators in an effort to halt the chemical application. The government went so far as to employ sharpshooters perched on water towers to provide protection for the fish eradicators.

This initial episode ended with a $9.2 million dollar settlement to the town of Portola from the Game and Fish Department and a still intact population of invasive predatory fish. All of this because of a bucket full of fish someone inconsiderately dumped into a lake just a few years prior.

|

| (Credit) |

|

| (Credit) |

Despite their differences, both sides agreed on one thing: the pike were to be eradicated. The town’s economy had stalled from a lack of trout and negative publicity, while Fish and Game had concerns of further pike spread. In an effort to complete the agreed upon task, measures beyond chemicals were considered, hence the pyrotechnic display that played out on the lake that explosive day in 1999. Nets, electrofishing, commercial fishermen, a fish dicing apparatus on the lake outflow, and a ramped up recreational contingency also contributed to the effort. Despite the efforts, the northern pike again prevailed, alive and voracious.

With all efforts failing, it became apparent that properly applied chemical efforts would be necessary. Through the use of communication, long term water quality monitoring, and advanced mapping and bathymetry techniques, the war was on. A northern pike effigy was constructed, and then subsequently destroyed as a display of a unified goal to eradicate the invasive predator.

|

| (Credit) |

While the northern pike was the successor of the initial battles, it finally lost the war in 2007. With proper application of thousands of gallons of rotenone in a drawn down lake, over 5 tons of northern pike met their demise in the final episode. In follow up samples, a few hardy bullhead catfish were all that remained in the lake, providing an almost clean slate for the stocking of thousands of trout.

|

| Treatment of the lake with rotenone was tracked with GPS technology (Credit) |

Today the lake boasts a successfully rebounding population of trout that both Portola residents and California Fish and Game officials are proud to display. Further, the salmon and steelhead in downstream habitats have one less possible intruder to contend with.

A positive outcome has been reached, but at a dramatic cost. It is important for anglers to understand the consequences of moving fish from one waterbody to another. Further, it is important for fisheries managers to properly consult constituents and stakeholders in eradication efforts to prevent unnecessary conflicts.

-Patrick Cooney

-Patrick Cooney

Further reading:

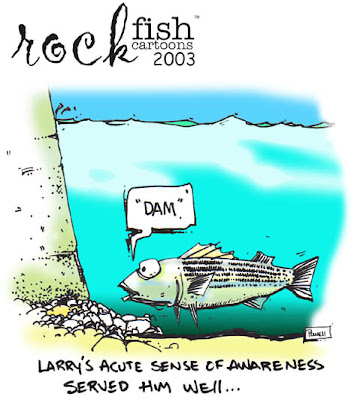

The Human Toll of Dams

As a fish person, I have heard the joke a hundred times, and each time I must pretend that it is the first time in order to not deflate the enthusiasm of the joke teller. You know the one, “What did the fish say when it ran into the wall?” I wait, not too long, not to short, then give a believable shrug of the shoulders like I am stumped. As they proclaim “Dam!”, I laugh like I have never heard it before.

|

| The Hoover Dam being built in the 1930s (Credit) |

The Golden Age of dam construction in the United States came to a grinding halt in the 1980s, and developing nations picked up the torch and continue carrying it today. Irrigation, hydropower, flood control, and water supply dominate the list of dam purposes, creating large impoundments that inundate vast areas of land.

|

| More than 80,000 dams in the US (Credit) |

Fish folk are often made acutely aware of the ecological impacts of dams on fish migration and habitat fragmentation, yet social impacts to humans have been mostly overlooked or disregarded until recently. With increasing global awareness of the social costs of large dam projects, the World Commission on Dams was formed in 1998, and subsequently published the first systematic assessment of large dams from around the world.

According to the report, some of the most challenging socioeconomic aspects of dam construction relate to the resettlement of individuals from the upstream catchment area and dam site. People are often displaced through coercion, force, or even by purposeful filling of reservoirs prior to the departure of those who are to be displaced. Resettlers seldom see their living conditions improve, and often slip further into poverty. Further, those downstream, especially those relying on natural flood plain function and fisheries, are often affected by reduced flows and are almost never compensated for their loss.

|

| More than one million people displaced by the Three Gorges Dam, China (Credit) |

Case studies from The World Commission on Dams demonstrate that a disproportionate amount of the adverse impacts caused by dams fall on poor and rural populations, subsistence farmers, indigenous peoples, ethnic minorities, and women. These groups, especially in developing countries, are underrepresented in politics, and seldom have equal human rights.

In the limited number of cases seen as successes, fewer instances of injustice and better resettlement outcomes were the result of the affected people and the stakeholders directly negotiating compensation packages. While compensation is not always seen as the most effective or appropriate option, people tended to feel more satisfied for having engaged in negotiations. Additionally, a positive outcome required full engagement of political, institutional, and community groups. So, next time I hear someone ask me the joke about the fish bumping its head, maybe I will not only be thinking of the fish. Would it be terrible if I were “that guy”, and answered their joke with: “Damn this disproportionately socially impacting pile of cement.” Leave a comment below telling us what would be fair compensation to make you leave your house and land so that a dam could be built.

Patrick Cooney

Further Reading: Human Rights in the Three Gorges Dam Resettlement World Commision on Dams Report

Further Reading: Human Rights in the Three Gorges Dam Resettlement World Commision on Dams Report

History of Sportfish Restoration

The Sport Fish Restoration Act is such a successful program in the United States that few anglers know that it took 11 years, an expensive world war, and overcoming a Presidential veto to eventually become law. Not only do we take for granted the immense struggle that was surmounted to enact this legislation, but we don't even associate it with the person who fought so hard for it in the first place.

The Pittman-Robertson Act of 1937 (also known as the Wildlife Restoration Act) was instrumental by setting aside 11% of all hunting equipment sales for establishing, restoring, and protecting wildlife habitats. The Act had some controversy attached to it, as politicians did not like to see excise tax revenues designated to a specific cause or project (politicians do not like to give up their power to spend funds over time as they see fit).

The Pittman-Robertson Act of 1937 (also known as the Wildlife Restoration Act) was instrumental by setting aside 11% of all hunting equipment sales for establishing, restoring, and protecting wildlife habitats. The Act had some controversy attached to it, as politicians did not like to see excise tax revenues designated to a specific cause or project (politicians do not like to give up their power to spend funds over time as they see fit).

Despite some political hiccups, the Wildlife Restoration Act passed and created immediate benefits. Considering the success, Congressman Frank H. Buck II of Vacaville, California introduced a similar bill in 1939 that would direct 10% from fishing equipment, artificial lures, and all other articles and devices for recreational fishing sales to fund fishing programs and protection of aquatic habitats.

This bill was a no-brainer considering the benefits of the Wildlife Restoration Act over the previous 2 years...right? Congressman Buck was completely surprised when unexpectedly the bill did not receive support, and died at the committee level. Again, excise taxes designated to a specific cause were blamed for the failure.

Dingell, Johnson, Wallop, and Breaux are the political names synonymous with the Sport Fish Restoration Act, but the name Frank Buck is nowhere to be found.

The story of Frank H. Buck II and the Sport Fish Restoration Act is like the story of the first day I went fishing. Neither of us had much success, and ultimately we were forced to learn about patience, close calls, and coming home empty handed. That first day of fishing doesn't show up in my photo album with pictures of big fish, but I credit that first day with creating a lifetime of fishing experiences. Similarly, despite being the first person to fight for sport fish restoration, Buck's name is not in the law books with the Sport Fish Restoration Act, but he should be remembered for creating the idea that has provided generations with fishing opportunities.

The Pittman-Robertson Act of 1937 (also known as the Wildlife Restoration Act) was instrumental by setting aside 11% of all hunting equipment sales for establishing, restoring, and protecting wildlife habitats. The Act had some controversy attached to it, as politicians did not like to see excise tax revenues designated to a specific cause or project (politicians do not like to give up their power to spend funds over time as they see fit).

The Pittman-Robertson Act of 1937 (also known as the Wildlife Restoration Act) was instrumental by setting aside 11% of all hunting equipment sales for establishing, restoring, and protecting wildlife habitats. The Act had some controversy attached to it, as politicians did not like to see excise tax revenues designated to a specific cause or project (politicians do not like to give up their power to spend funds over time as they see fit).Despite some political hiccups, the Wildlife Restoration Act passed and created immediate benefits. Considering the success, Congressman Frank H. Buck II of Vacaville, California introduced a similar bill in 1939 that would direct 10% from fishing equipment, artificial lures, and all other articles and devices for recreational fishing sales to fund fishing programs and protection of aquatic habitats.

|

|

|

| Buck, second from left, at Social Security Act signing with FDR (Credit) |

|

But wait, Buck's bill passed! Could it be that sport fish restoration would become a cornerstone project, providing millions of dollars to protect habitat and increase angling opportunities? Would Buck's name be the standard bearer for this Act?

In a cruel twist for Frank Buck and for sport fish restoration, other politicians did not vote yes on the bill because they saw an inherent value in restoring fish. Rather, they saw a quick way to make more money for the war effort, and they modified and amended the bill so that the extra taxes from the sales of fishing equipment were deposited directly into the General Fund to help finance the war. Buck fought to change this, but it was too late and the war was too powerful of a cause.

|

In a final blow to the possibility of Buck's name being attached to the Act, Buck died September 17, 1942. However, his name does live on, and is the title bearer of an incredibly worthy cause that has furthered the education of almost 300 young students. Almost 50 years after his death, in 1990, his wife, Eva, established the Frank H. Buck Scholarship to help students from central California attend higher education universities.

As Eva allowed Frank Buck to provide after his death, others saw the need for sport fish restoration to provide once its original champion had passed. Little did they know that they were in for a struggle similar to the one Frank had faced.

|

| John Dingell (Credit) |

Upon completion of the war in 1945, rods, reels, and artificial lures continued to be taxed, but the money continued to go to the General Fund. Around 1947, Congressman John Dingell, Sr. of Michigan showed up on the scene, and attempted to make modifications to appease some previous concerns that fishing tackle companies had with the collection of taxes.

|

| Edwin Johnson (Credit) |

As expected in the tumultuous world of politics, the bill met the same fate as when Buck had tried, and failed. Yet service members were returning from war and began taking a large interest in recreational angling. Sport fishermen began putting their support behind the restoration effort, and Senator Edwin Johnson teamed with Congressman Dingell to introduce identical bills in each chamber in 1949. The bills received sweeping support and passed, but of course, it would not come that easy.

|

| Truman grouper fishing in Key West, Florida (Credit) |

Harry S. Truman succeeded as the 33rd President of the United States of America following the death of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and vetoed the bill in 1949 because of reluctance, again, to designate an excise tax for specific purposes.

Unfortunate for Truman, and fortunate for sport fish restoration, the movement had received tremendous support by this time from recreational anglers. In 1950, Dingell and Johnson put the bill forth for the final time, where it passed, and was reluctantly signed by President Truman as the Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration Act on August 9th of that year to invest anglers' tax dollars in state sport fishing restoration projects.

In the early 1980s, it became apparent that further funding was necessary to meet the increasing needs of the angling community, and in 1984 Senator Malcolm Wallop and Congressman John Breaux successfully amended the original Act by expanding the list of taxed items to include all fishing tackle, fuel used by motorboats, and import duties on fishing tackle and boats. Over the years, additional funding was secured, but no further names have been associated.

|

| John Breaux (Credit) |

|

| Malcolm Wallop (Credit) |

We are currently celebrating the 75th anniversary of the Wildlife Restoration Act. The logo below implies that both wildlife and sport fish restoration have been taking place for 75 years. Yet, we will have to wait another 13 years to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Sport Fish Restoration Act. Had congress initially recognized the long term value when Frank Buck first introduced the bill, we would only be waiting 2 more years.

As you go about your work funded by these acts, or you are enjoying the outdoors fishing with your friends and family, it is important to recognize the benefits that these acts and individuals have provided. The next time you hear someone refer to Dingell-Johnson, Wallop-Breaux, or sport fish restoration, do not forget the efforts of unrecognized people like Frank H. Buck, and give credit to those who are good stewards of the resource.

-Patrick Cooney

Video celebrating 75 years of restoration

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)